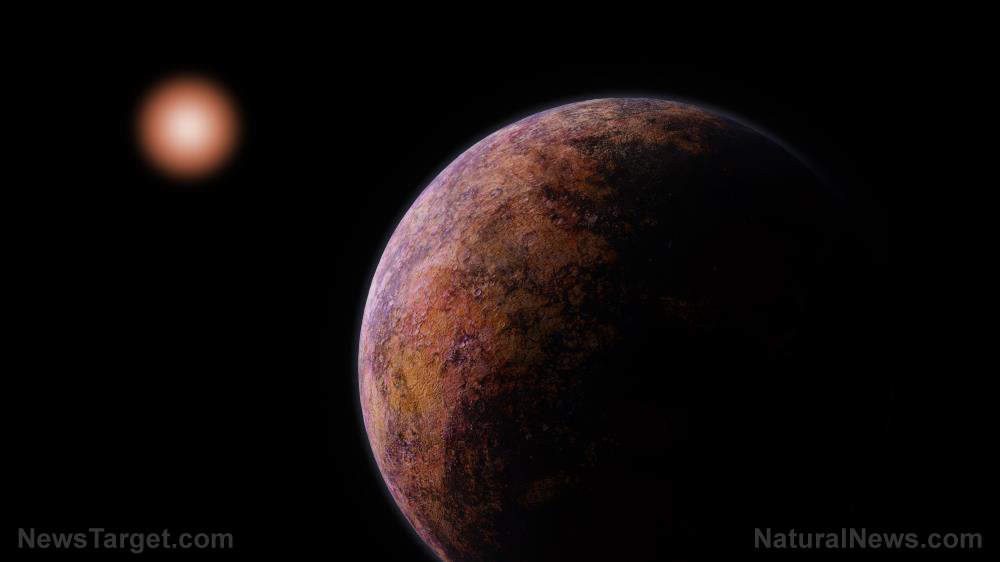

Dwarf planet Ceres may have saltwater beneath its surface, researchers say

08/14/2020 / By Virgilio Marin

Reservoirs of saltwater may be lurking beneath the surface of Ceres, the dwarf planet closest to Earth, according to recent images taken by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)’s Dawn spacecraft.

Dawn orbited Ceres from 2015 to 2018 until it ran out of fuel. In its final months, it flew about 20 miles above the dwarf planet and captured images of Occator, a 57-mile crater that formed due to a meteorite impact 20 million years ago. At its center, regions of bright spots can be seen from space, composed of natural salts that make them highly reflective.

After analyzing gravity in these regions, scientists found a low-density region beneath the Occator that appears to be a briny slush of water.

“The existence of a deep-seated brine reservoir beneath Occator is supported by recent results from gravity data,” said Carol Raymond of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Raymond is the principal investigator for the Dawn mission.

The analyses of the Dawn data are published in the journals Nature Astronomy, Nature Geoscience and Nature Communications.

Briny waters erupt through impact-induced fractures

Ceres was initially called an asteroid until scientists reclassified it as a dwarf planet in 2006, arguing that Ceres was too big and too different from its rocky neighbors in the asteroid belt.

One of its fascinating features is the regions of bright, reflective spots that were discovered long before Dawn arrived at Ceres. When Dawn arrived at the dwarf planet, it captured high-resolution images of two distinct, highly reflective areas within these regions, which were named Cerealia Facula and the Vinalia Faculae.

Dawn also mapped the dwarf planet’s gravity field, which displays a low-density area just outside the Occator. Analysis of the gravity field suggests the existence of a blob of low-density material about 25 miles below the surface and hundreds of miles in size. After cross-analyzing the data on gravity against other available observations, the researchers concluded that the low-density region is most likely a reservoir of briny water.

They posited that the briny waters were caused by the meteorite impact that created Occator: The impact melted ice underground in a small reservoir that mostly froze again within a few million years. Furthermore, the impact likely fractured the crust. These fractures served as conduits for brines moving upward and erupting on the surface, leaving behind a highly reflective salt crust on the surface after the water evaporated.

Further analysis also suggests that the bright regions formed about 2 million years ago – far too recent to have come from the melt from the initial meteorite impact.

“In order for the bright deposits to form later, relative to the impact event, you need to be able to transport the briny material to the surface somehow over an extended period of time,” said Anton Ermakov of the University of California, Berkeley, who works with the Dawn team.

Although the data is not enough to determine what the reservoir looks like or how big it really is, Ermakov said this interpretation revolving around crustal fractures is consistent with the survey data on gravity and other measurements of the surface.

Brine continues to percolate

Scientists also argue that the geologic activity driving brine upward is still active after finding chloride salts in Cerealia Facula.

“These salts are very efficient in maintaining Ceres’ warm internal temperature and lowering the temperature of the brines, in which case ascending salty fluids may exist today,” said Maria Cristina De Sanctis of the National Institute of Astrophysics in Rome.

Salts bearing water quickly dehydrate on the surface of Ceres. But measurements show they still have water, which means that the fluids likely reached the surface very recently. This suggests that liquid is present below the region of the Occator and that the transfer of material from the deep interior is ongoing. (Related: Search for origin of life intensifies as NASA probes alien oceans on moons in the outer solar system.)

The unusual assortment of conical hills also points to ongoing geologic activity in Ceres. These features are similar to Earth’s pingos — small ice mountains in the polar regions that were formed by frozen pressurized groundwater.

Planetary scientist Julie Castillo-Rogez of the California Institute of Technology commented on the implications of the study: “The next ten years of dwarf planet exploration requires focus to be brought onto habitability through time in these evolved oceans – which are likely to be rich in organic matter.”

Space.news has more on worlds beyond our own.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: alien life, asteroid belt, Ceres, discovery, Dwarf planet, meteorite impact, NASA, Space, water in space

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 SPACE.COM

All content posted on this site is protected under Free Speech. Space.com is not responsible for content written by contributing authors. The information on this site is provided for educational and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional advice of any kind. Space.com assumes no responsibility for the use or misuse of this material. All trademarks, registered trademarks and service marks mentioned on this site are the property of their respective owners.