Hackers could shut down satellites – or turn them into weapons

03/06/2020 / By Michael Alexander

There are currently around 2,000 satellites orbiting the earth, each one beaming down signals which allow us to enjoy our favorite television shows, movies and even connect to the internet.

Elon Musk’s Space Exploration Technologies Corp. or SpaceX, which launched 242 satellites as of the end of January, plans to deploy about 42,000 more over the next decade. These new satellites are part of Starlink, a network that SpaceX is developing in hopes of providing Internet access to remote corners of the globe. According to SpaceX, these new satellites are also seen to help monitor the environment, as well as improve global navigation systems.

In the wrong hands, however, they can easily turn into weapons.

According to a piece by William Akoto of the University of Denver, this is because of the lack of cybersecurity standards and regulations for commercial satellites, not just in the U.S. but also, internationally.

Akoto said this lack of regulation makes the satellites highly susceptible to cyberattacks. (Related: Thousands of new satellites to carpet bomb the planet with 5G radiation… and there’s nowhere you can hide.)

“If hackers were to take control of these satellites, the consequences could be dire. On the mundane end of the scale, hackers could simply shut down satellites, denying access to their services. Hackers could also jam or spoof the signals from satellites, creating havoc for critical infrastructure. This includes electric grids, water networks and transportation systems,” Akoto said in his column.

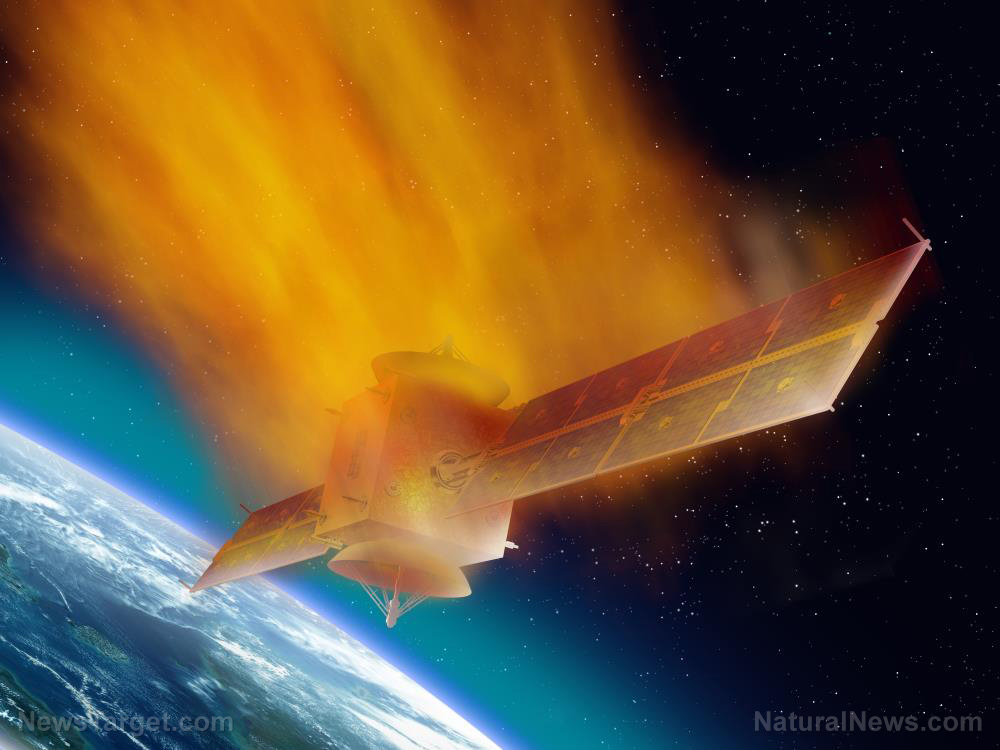

There are worse scenarios as well: According to Akoto, since some of the new satellites have thrusters that allow them to speed up, slow down and change direction in space, the consequences would be nothing short of catastrophic if hackers took control of these steerable satellites.

“Hackers could alter the satellites’ orbits and crash them into other satellites or even the International Space Station,” Akoto said.

Satellites: A hack job

As it turns out, there’s more than one way to hack a satellite.

This is because most satellites, such as the small, low-powered CubeSats, use common, off-the-shelf technology in order to keep production costs low. However, this means that hackers can not only easily analyze them for vulnerabilities; they can also draw on open-source technology to insert back doors and other vulnerabilities into the satellites’ software.

In addition, the production, operation and maintenance of satellites are each handled by different organizations or companies. This translates to even more opportunities for hackers to force their way into satellite systems.

To make matters even worse, hacking satellites is relatively easy, since the units are typically controlled using computers located in ground stations. These computers can then be easily exploited by hackers and subsequently re-programmed to send malicious commands to the satellites themselves.

This echoes a 2018 statement by Ruben Santamarta, a researcher for the information security firm IOActive, during a presentation at the Black Hat information security conference in Las Vegas. Santamarta previously carried out a study exploring theoretical vulnerabilities in modern satellite systems.

In his study, Santamarta found that a number of popular satellite communication systems are vulnerable to attacks, which could pose a safety risk for military and maritime users.

“The consequences of these vulnerabilities are shocking,” Santamarta said. “Essentially, the theoretical cases I developed four years ago are no longer theoretical.”

According to Santamarta, the worst-case scenario is that hackers could carry out “cyber-physical attacks” by turning satellite antennas into weapons that operate like microwave ovens.

Hacked satellites: a scary reality

Cyberattacks on satellites, contrary to what people might think, are not limited to science fiction.

According to Akoto, one particular case happened in 1998, when hackers reportedly took control of the U.S.-German ROSAT X-Ray satellite by gaining access to computers at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. After gaining control of the satellite, the hackers then instructed it to turn its solar panels directly at the sun, effectively destroying its batteries and ruining its internal mechanism.

Since then, the incidents have become more concerning: In 2005, cyber break-ins occurred at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where space shuttles are launched; at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland where satellites and spacecraft are controlled; and at the Johnson Space Center in Texas, which is home to Mission Control for the International Space Station.

Expert says government should beef up involvement

In order to avoid potential attacks, Akoto said the best course of action would have to be strong government involvement in the development and regulation of cybersecurity standards for satellites and other space assets.

“Congress could work to adopt a comprehensive regulatory framework for the commercial space sector,” Akoto said, adding that Congress can pass legislation that requires satellite manufacturers to develop a common cybersecurity architecture.

Akoto, in his piece, also recommends increased transparency not just when it comes to the reporting of all cyber breaches involving satellites but also on which space-based assets are deemed “critical” in order to prioritize cybersecurity efforts.

Akoto noted, however, that whatever steps the government and industry will take, it is imperative to act now.

“It would be a profound mistake to wait for hackers to gain control of a commercial satellite and use it to threaten life, limb and property – here on Earth or in space – before addressing this issue,” Akoto said.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: dangerous tech, Elon Musk, EMF, Glitch, hacking, microwave, privacy, radiation, satellites, Space, SpaceX, surveillance, telecommunications, weapons technology, WiFi

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 SPACE.COM

All content posted on this site is protected under Free Speech. Space.com is not responsible for content written by contributing authors. The information on this site is provided for educational and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional advice of any kind. Space.com assumes no responsibility for the use or misuse of this material. All trademarks, registered trademarks and service marks mentioned on this site are the property of their respective owners.