Can life find a way? Tiny planet around a white dwarf may hold clues to understanding habitable worlds in the universe

08/31/2019 / By Edsel Cook

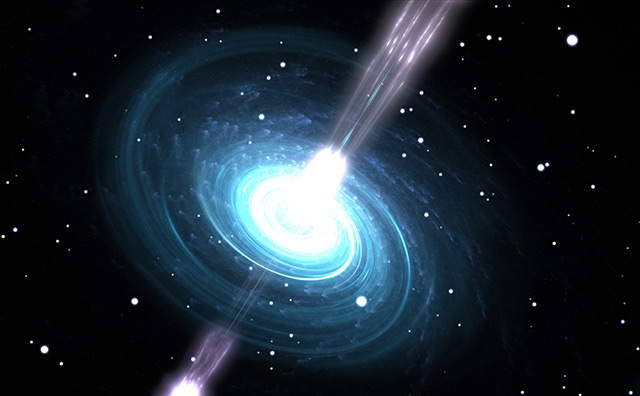

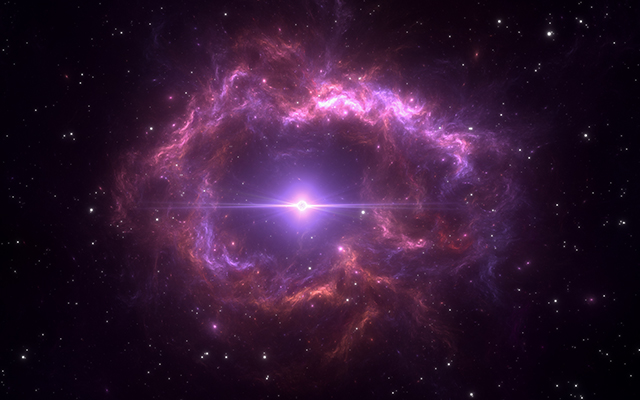

The star called SDSS J122859.93+104032.9 died long ago, and its death spasms devoured the planets that circled it. But U.K. researchers recently found a surviving planetesimal zipping through the diminishing debris disk around the white dwarf star.

A fragment that broke off its original exoplanet during the latter’s destruction, the planetesimal showed high levels of iron and nickel. It orbited its primary star at an extremely close range and breathtaking speed, taking just two hours to circle the white dwarf star.

Researchers from the University of Warwick led the effort that discovered the planetesimal. By examining faint changes in the light given off by SDSS J122859.93+104032.9, they spotted the gases released by the tiny solid body orbiting it.

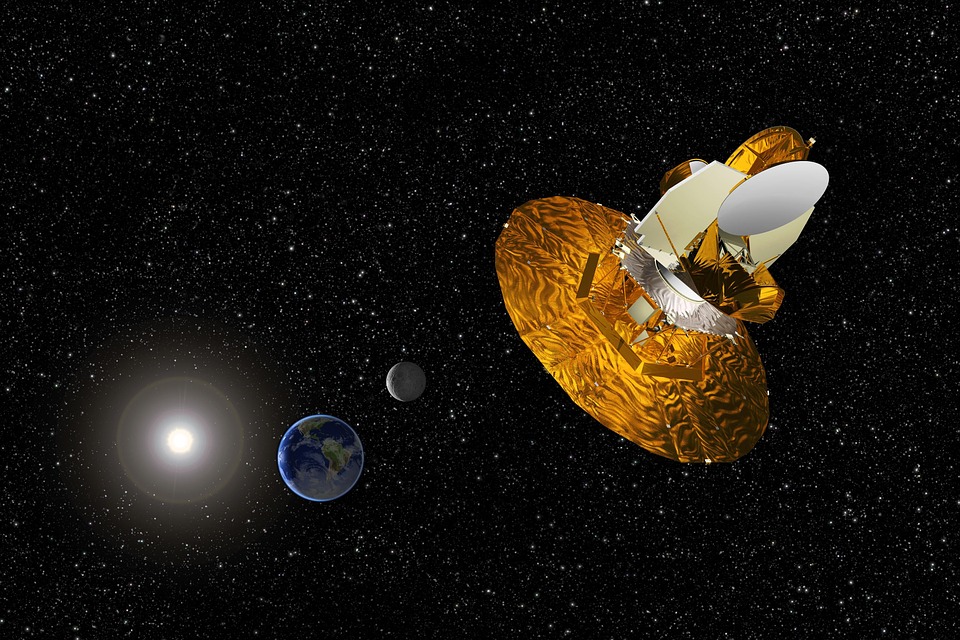

The white dwarf star and its planetesimal lay 410 light-years away from Earth. The research team observed the devastated star system with the Gran Telescopio Canarias in La Palma, Spain.

Their initial estimate of the size of the planetesimal indicated a diameter of at least one kilometer. The fragment might turn out to be as big as the largest asteroids in the solar system, which measure more than a hundred miles across. (Related: Straight out of sci-fi? Researchers say that aliens use black holes to travel.)

White dwarf stars offer a glimpse of the fate of our sun

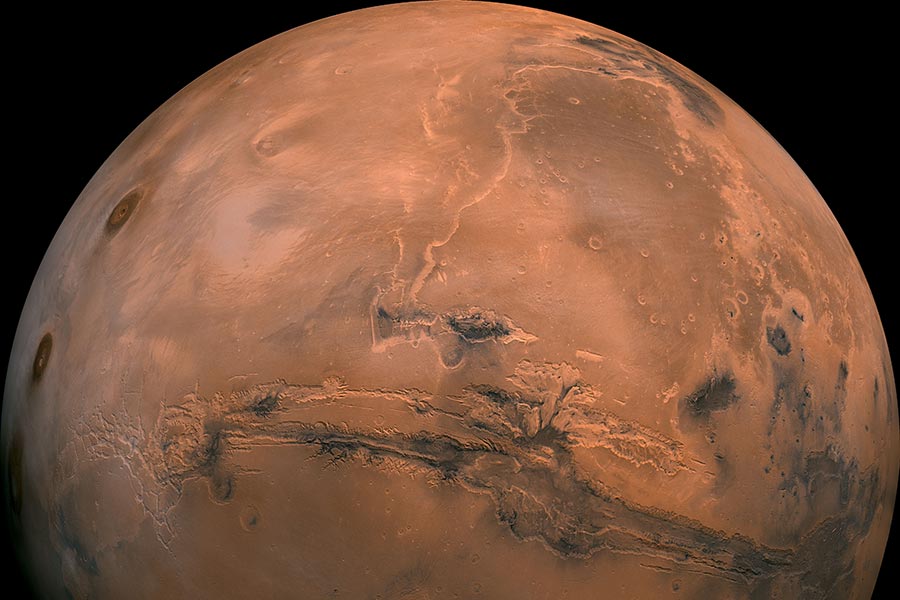

The Warwick researchers also investigated the debris disk around SDSS J122859.93+104032.9. They reported the presence of iron, magnesium, oxygen, and silicon – the four vital building blocks of most rocky bodies such as the Earth.

Furthermore, they found a ring of gas from the planetesimal. They theorize that the emissions either originated from the solid body itself or from the dust created by its collision with smaller debris during its trip through the disk.

White dwarfs are all that remain of stars like the sun. After expending all of their fuel and losing most of their layers, only the thick core survives, growing colder as time passes. Indeed, SDSS J122859.93+104032.9 grew so small that the planetesimal is well within the starting radius of the full-sized star.

As for the planetary fragment itself, it might have come from a sizable rocky planet in the outer reaches of the system. When the star started to cool down, the original exoplanet would have been ripped apart.

“The star would have originally been about two solar masses, but now the white dwarf is only 70% of the mass of our Sun,” explained Warwick researcher Dr. Christopher Manser. “It is also very small – roughly the size of the Earth – and this makes the star, and in general all white dwarfs, extremely dense.”

A newly discovered planetesimal may have broken away from the core of a rocky planet

A typical white dwarf star exerts the same gravitational force as 100,000 Earths. SDSS J122859.93+104032.9 would have torn apart most asteroids that drifted too close – yet its planetesimal continued to defy destruction.

“The planetesimal we have discovered is deep into the gravitational well of the white dwarf, much closer to it than we would expect to find anything still alive,” noted Manser’s co-author, Warwick researcher Boris Gaensicke. “That is only possible because it must be very dense and/or very likely to have internal strength that holds it together, so we propose that it is composed largely of iron and nickel.”

Gaensicke proposed that the planetesimal came from the core of a rocky planet. Such an origin might explain its incredible internal strength and rich iron-nickel content.

If true, the original planet might have spanned at least several hundred kilometers in diameter, the minimum size for differentiation. During that process, heavier elements would sink deeper into the body and form a metallic core.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: asteroids, astronomy, cosmic, dwarf star, exoplanets, outer space, planetesimals, planets, Space, star system, sun, white dwarf star

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 SPACE.COM

All content posted on this site is protected under Free Speech. Space.com is not responsible for content written by contributing authors. The information on this site is provided for educational and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional advice of any kind. Space.com assumes no responsibility for the use or misuse of this material. All trademarks, registered trademarks and service marks mentioned on this site are the property of their respective owners.