Astronomers develop new method to detect mysterious radio bursts from billions of light years away using AI

04/13/2021 / By Joven Gray

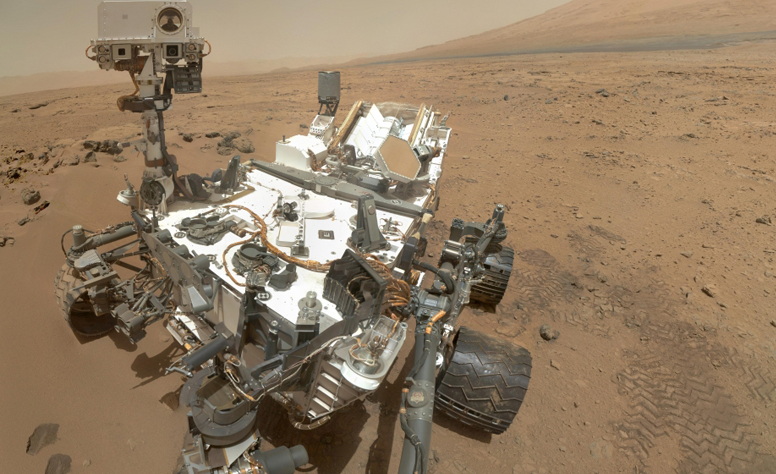

A doctorate student from Australia developed an automated system to detect fast radio bursts (FRBs), or mysterious and powerful flashes from outer space. In his report, Wael Farah from the Swinburne Institute of Technology discussed how he built the UTMOST FRB search program, an automated system for capturing FRBs using artificial intelligence (AI) at the Molonglo Radio Observatory.

Farah and his colleagues were able to record five FRBs using the system. These radio waves came from a source approximately 3.6 billion light-years away from the Earth. In particular, one of the FRBs they captured is said to be the most energetic and broadest burst ever recorded.

FRBs are intense and unexplained radio signals that reach the Earth’s atmosphere from sources millions of light-years away. Although FRBs last only for milliseconds, these resound in the sky together with other radio pulsars in the galaxy.

“It is fascinating to discover that a signal that traveled halfway through the universe, reaching our telescope after a journey of a few billion years, exhibits complex structure, like peaks separated by less than a millisecond,” said Farah.

The bursts are detected by the Molonglo Observatory’s telescope, and Farah’s device captures them. His invention also has the ability to sort FRBs out of all the other noises that the device picks up.

“Wael has used machine learning on our high-performance computing cluster to detect and save FRBs from amongst millions of other radio events, such as mobile phones, lightning storms, and signals from the Sun and from pulsars,” said project scientist Chris Flynn.

“Molonglo’s real-time detection system allows us to fully exploit its high time and frequency resolution and probe FRB properties that were previously unobtainable,” said project leader Matthew Bailes.

Farah’s project is a collaboration between his school and the University of Sydney, which owns the telescope in Molonglo.

Discovery of the FRBs and possible source

The first FRB arrived on Earth on July 24, 2001 and has a length of five milliseconds. However, astronomers believe FRBs have been traveling in the universe some 1.6 billion years ago when a dead star released these bursts in a direction towards the planet.

In addition, the 2001 event was not recognized in history books until 2006, when an undergraduate student from West Virginia University, together with his adviser, discovered the signal from archival data from the Parkes radio telescope in Australia. With their discovery, the FRB from 2001 was dubbed as the “Lorimer burst,” after the student’s adviser, Duncan Lorimer.

Since the FRBs have relatively short durations, scientists have a hard time catching and determining their possible sources. (Related: Mysterious blobs of radio emissions found floating in space.)

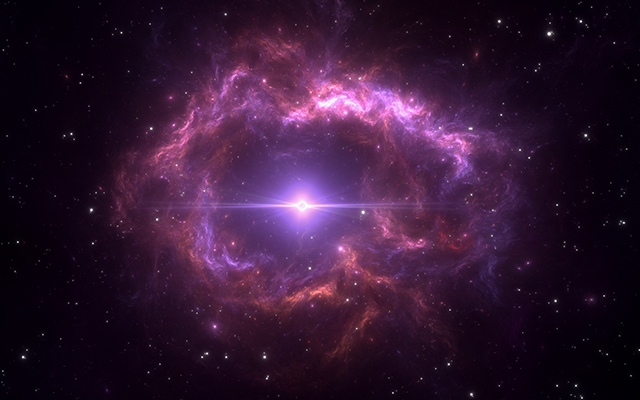

One suspected source of these bursts is magnetic stars, also called “magnetars” by astronomers. According to them, these are remnants of massive dead stars that are highly magnetic.

In April 2020, X-rays, gamma rays and a blast of an FRB were spotted by astronomers from a magnetar, which they named SGR 1935+2154. According to the discoverers, this magnetar is situated near the center of the Milky Way Galaxy and about 30,000 light-years away from Earth. This discovery was published in the journal Nature in November 2020.

“This discovery paints a picture that some — and perhaps most — of these fast radio bursts from other galaxies also originate from magnetars,” said study co-author Christopher Bochenek in a press conference.

According to Bochenek and his team, this is the first FRB detected in the Milky Way, the first FRB accompanied by other detectable radiations and the first FRB that can be attributed as released by a single source.

Visit Space.news to learn more about the discoveries in the universe.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: AI, artificial intelligence, breakthrough, cosmic, discoveries, fast radio bursts, FRBs, future science, future tech, innovations, inventions, research, Space, space exploration

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 SPACE.COM

All content posted on this site is protected under Free Speech. Space.com is not responsible for content written by contributing authors. The information on this site is provided for educational and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional advice of any kind. Space.com assumes no responsibility for the use or misuse of this material. All trademarks, registered trademarks and service marks mentioned on this site are the property of their respective owners.