Study: Fiery “airburst” of superhot gas crashed into Antarctica millions of years ago

04/03/2021 / By Virgilio Marin

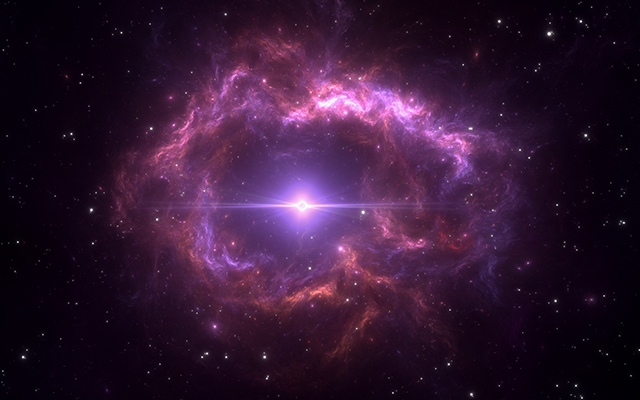

A study published March 31 in the journal Science Advances found that an asteroid the size of a football field exploded over Antarctica roughly 430,000 years ago. The study, led by Belgian geoscientist Matthias Van Ginneken, showed that this “airburst” event produced a fiery ball of hot gas that traveled as quickly as the asteroid.

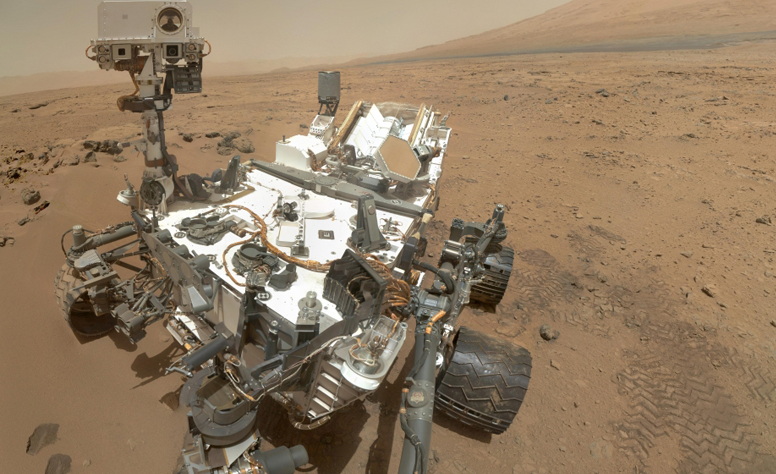

Van Ginneken and his colleagues launched an expedition to Walnumfjellet in Sor Rondane Mountains of Queen Maud Land, which is located south of Africa on the eastern side of Antarctica. The researchers found strange-looking mineral particles that turned out to be micrometeorites – extremely tiny meteorites that are the size of dust particles – from the airburst.

“To my great surprise, I found these very weird looking particles that did not look like terrestrial particles … but they didn’t look like micrometeorites either,” Van Ginneken, a researcher at the University of Kent in the U.K., told Live Science.

Ordinary micrometeorites resemble fine dust, but around half of the samples looked like tiny stones fused together. Some were speckled with distinct matter while others bore snowflake-like markings, Van Ginneken said.

Examining Antarctic micrometeorites

Van Ginneken and his team conducted thorough chemical analyses of the particles. They also searched the literature for reports of similar particles and created numerical models of them.

The team’s analyses showed that the particles measured around 0.004 to 0.01 inches across and mostly contained the minerals olivine and iron spinel, which created the snowflake-like patterns on some of the samples. Both minerals were fused together by a small amount of glass.

This mineral composition closely resembled the composition of a class of meteorites known as CI chondrites, confirming that the samples contained asteroid material. The substantial amounts of nickel in the particles also pointed to an extraterrestrial origin because nickel is not abundant on Earth’s crust, Van Ginneken explained.

Past reports of meteorite impacts showed that similar particles had been captured in ice cores from other Antarctic regions. By comparing the newfound particles to these older samples, the researchers estimated that the Walnumfjellet micrometeorites formed roughly 430,000 years ago. (Related: For the first time, an asteroid has been found with essential ingredients for life.)

The researchers determined that the particles formed in the atmosphere since they were quite rich in oxygen compared to typical chondrites. But the particles lacked oxygen-18, a form of the element that’s denser than usual due to its extra neuron. This indicated that the particles interacted and mixed with Antarctic ice since the latter contains very little oxygen-18.

Airbursts produce destructive plumes of superhot gas

Van Ginneken and his colleagues calculated the size of the particles’ parent asteroid. In so doing, they were able to work out how the unusual-looking particles came to be.

The samples’ fused appearance hinted that the cloud of hot gas in which they formed was very large and dense, which allowed the minerals to collide and melt into one another on their way to the ground. This suggested that the parent asteroid was likely between 328 feet and 492 feet in diameter.

The team’s numerical models showed that an asteroid of this size would not reach the ground. Instead, it would vaporize into a cloud of superheated meteoritic gas. But instead of scattering in the atmosphere, the cloud of gas would continue barreling toward the surface at a similar rate to the original asteroid.

“This very dense, incandescent plume that would reach the surface, this is extremely destructive. This could destroy a large city in a matter of seconds, and do severe damage over hundreds of kilometers,” Van Ginneken said.

In 2013, a destructive airburst event occurred over the city of Chelyabinsk in Russia. A meteor the size of a six-story building exploded in the atmosphere, producing trails of rock fragments that continued to travel downward. While these rocky trails did not cause much damage, the explosion generated shockwaves that shattered windows and injured thousands.

The researchers recommended focusing planetary defense efforts on smaller asteroids (rocks between 32 to 656 feet wide) than much larger impactors because smaller space rocks touch down on the planet much more often. Should such an asteroid hurtle towards a small country, mass evacuation would likely be needed to protect people from an airburst, Van Ginneken said. (Related: NASA chief: Asteroid strikes are not like the movies, world powers should prepare for impact.)

Learn more about what would happen if an asteroid big enough to cause damage barreled toward Earth at Disaster.news.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: airbursts, Antarctica, asteroid impact, asteroids, Chelyabinsk Event, disaster, discoveries, meteorites, meteors, micrometeorites, natural disasters, planetary defense, Space, space research, Unexplained, weird science

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 SPACE.COM

All content posted on this site is protected under Free Speech. Space.com is not responsible for content written by contributing authors. The information on this site is provided for educational and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional advice of any kind. Space.com assumes no responsibility for the use or misuse of this material. All trademarks, registered trademarks and service marks mentioned on this site are the property of their respective owners.