With the presidential election over, the focus in Washington, D.C., can finally turn back to policy and legislation.

Article by Mike Wall

Most of the conversations between President-elect Trump and Congress will probably involve immigration, health care, the economy and other similarly high-profile issues. But the nation’s future path in space will also be under consideration — and it will probably generate some spirited debate.

One of the hottest topics will likely be the direction of NASA’s human-spaceflight program, said Brian Weeden, a technical adviser for the nonprofit Secure World Foundation. [Gallery: 50 Years of Presidential Visions for Space Exploration]

In his first term, President Barack Obama canceled George W. Bush’s moon-oriented Constellation program and instructed NASA to get astronauts to a near-Earth asteroid by 2025, then on to the vicinity of Mars by the mid-2030s.

To meet the first part of that directive, NASA devised the Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM), which will pluck a boulder off a near-Earth asteroid using a robotic probe. This spacecraft will then haul the boulder to lunar orbit, where it will be visited by astronauts.

But ARM has its share of detractors, and some of them occupy positions of power on Capitol Hill. For example, earlier this year, the House of Representatives’ Appropriations Committee proposed denying funding to the mission.

“The Committee believes that neither a robotic nor a crewed mission to an asteroid appreciably contribute[s] to the overarching mission to Mars,” committee members wrote in a report. “Instead, NASA is encouraged to develop plans to return to the moon to test capabilities that will be needed for Mars, including habitation modules, lunar prospecting and landing and ascent vehicles.”

This asteroid-versus-moon argument isn’t likely to end anytime soon, especially since most of the international human-spaceflight community prefers the lunar option, Weeden said.

And that brings up another issue, he added: Just how much international cooperation will there be on NASA’s envisioned journey to Mars and other big projects? Who will the partners be? Could China be involved, even though U.S. law currently prohibits NASA from working with China to any significant degree?

“That’s a very big civil-space public policy question that the next administration will most definitely be tackling,” Weeden said last week during a presentation with NASA’s Future In-Space Operations working group. [5 Manned Mission to Mars Ideas]

Also potentially on the docket, he said, will be the further mapping out of NASA’s relationship with the private sector.

The George W. Bush and Obama administrations set NASA on a path that hands over many activities in low-Earth orbit (LEO) to private companies, theoretically freeing up the space agency to focus on more ambitious efforts, like getting people to Mars. For example, SpaceX and Orbital ATK currently fly robotic cargo missions to the International Space Station for NASA, and SpaceX and Boeing should start flying American astronauts to and from the orbiting lab in a year or two.

“That raises a bigger question about, Are there activities NASA has historically done that are perhaps better suited for the private sector to do?” Weeden said. “If so, how do you make that transition, and what does that mean for the future of NASA and NASA’s workforce, and how NASA is organized?”

As the cancellation of Constellation and the push to scrap ARM show, NASA is often pulled this way and that by the president and Congress — not an ideal situation for an agency that’s trying to plan out a crewed Mars mission and other activities 20 or 30 years in the future. So the next administration may investigate ways to ensure more policy stability for NASA, Weeden said.

The NASA administrator is currently nominated by, and serves at the pleasure of, the president. Some people have suggested that the NASA chief should instead be appointed by a panel, and/or serve a fixed term. Such changes would help shield the agency from partisan politics, the idea goes.

There are other important space-policy questions that must be dealt with at some point, Weeden said. For example, which federal agency (or agencies) should regulate the nascent asteroid-mining industry and other near-future space activities, such as private space stations and commercial moon outposts? Should the United States be in charge of cleaning up space junk, or should an international coalition lead this effort?

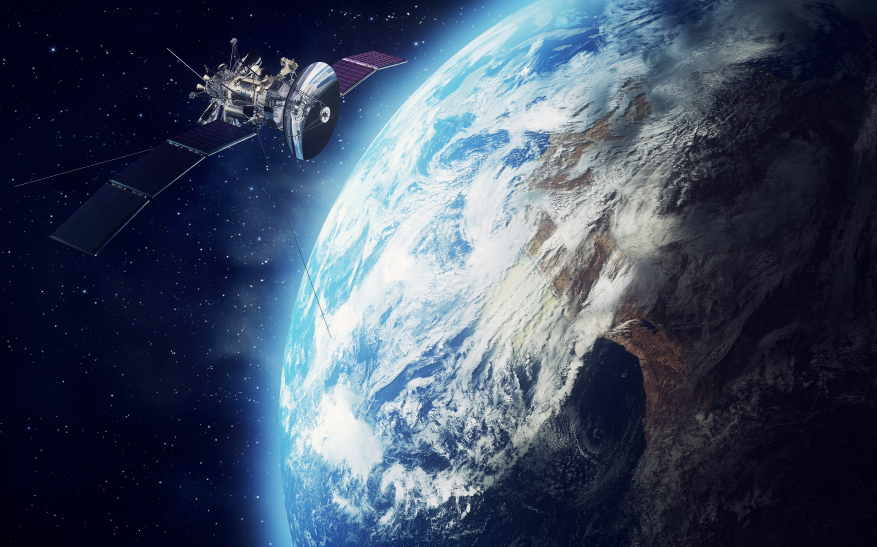

Then there’s the national-security realm. Much of the United States’ military might is based on the nation’s dominance in space; for example, sharp-eyed spy satellites often give American warfighters a clearer view of the battlefield than their adversaries can get.

But other countries are increasingly contesting this dominance by developing their own advanced spacecraft and, in some cases, anti-satellite capabilities, experts have said.

“There’s much more of a case that in future conflicts, there’s probably going to be a space element of the conflict,” Weeden said.

So the U.S. military is assessing how best to deal with this developing situation, he added.

“There’s a discussion about, should the U.S. develop new offensive counterspace capabilities of its own, in part to deter adversaries, or perhaps to counter their own capabilities?” Weeden said. “And related to that: How might the U.S. deter potential adversaries such as Russia and China from kinetic attacks on space [assets] in a future conflict? And then, how best to leverage commercial industries and allies in that mix of resilience and assurance?”

President-elect Trump and Congress will therefore have a lot to talk about when it comes to space. And they may have fewer arguments than we’re used to seeing, now that the presidency, House and Senate are all in Republican hands.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us@Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Read more at: space.com